每日外闻93

Risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease breaks the blood–brain barrier

阿尔茨海默症的危险因子打破了血脑屏障

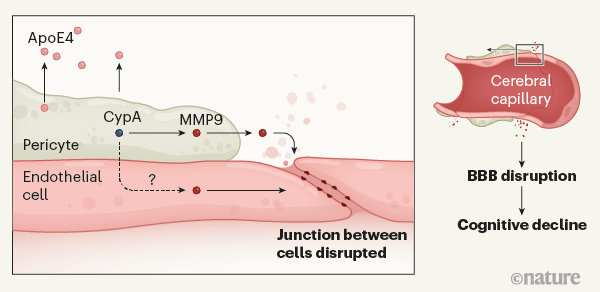

作者清晰的回顾了相关问题的研究,主要的结论为下面这张图所示的那样:

携带APOE4突变的的人罹患阿尔茨海默氏病的风险更高。 Montagne等人提供的证据表明,ApoE4蛋白被称为周细胞(pericytes)的细胞分泌,该细胞与位于血脑屏障(BBB)处脑毛细血管的内皮细胞(endothelial cells)邻接。分泌的ApoE4激活周细胞中的亲环蛋白A(CypA)。这触发了下游信号传导途径,该信号传导途径涉及周细胞中以及内皮细胞中炎性蛋白基质金属蛋白酶9(MMP9)的激活。这引起相邻内皮细胞之间连接的破坏,从而在参与学习和记忆的大脑区域打开了血脑屏障。 BBB的破坏与认知能力受损有关,尽管将两者联系起来的机制尚不清楚。

-----

这些发现为APOE4带来了新的亮点,这与人们普遍认为该基因变异仅通过促进Aβ和tau蛋白积累而导致阿尔茨海默病的想法背道而驰。相反,相反,似乎血脑屏障功能障碍可以解释APOE4携带者易患阿尔茨海默病的原因。作者的发现也可以解释为什么APOE4携带者在中风或创伤性脑损伤后的预后比携带其他APOE突变的人更差。然而,随着阿尔茨海默病的发展,APOE4也可以减缓Aβ和τ的清除,加剧了认知的下降。

更惊人的发现是,APOE4和APOE3携带者之间认知障碍的早期驱动因素存在差异。Montagne和他的同事的发现表明,在携带最常见的APOE突变APOE3的人群中,CypA通路的激活和周细胞损伤可能与认知障碍无关。但是,由与周细胞无关的因素引起的血脑屏障的屏障功能障碍(例如,由Aβ引起的内皮细胞损伤)是否导致APOE3携带者的认知障碍尚不清楚。血脑屏障在APOE2携带者中的作用,在目前的研究中没有被评估,也仍然是未知的。尽管与其他APOE突变相比,APOE2与降低阿尔茨海默病的风险有关,但这不太可能是APOE2突变致使血脑屏障的结构变强,因为APOE2携带者有更高的微出血风险,提示该突变携带者的血管更加脆弱。

血脑屏障的崩溃是否会导致认知障碍以及如何导致认知障碍还有待进一步的研究确定。它是疾病过程的原因还是结果?来自小鼠的证据表明,血液中的某些蛋白质,如纤维蛋白原,会破坏神经元之间的突触连接。但是这些蛋白质在人脑中的致病作用还没有被证实。

撇开这些问题不谈,Montagne等人已经拓展了我们对APOE4如何促进认知障碍的理解。他们还证明了不同的APOE状态可以通过不同的机制促进疾病。深入了解基因变异是如何影响阿尔茨海默氏症这种普遍存在的不治之症的,可能对更个性化的治疗方法至关重要。

以下为原文:

These observations cast new light on APOE4 that runs contrary to the widely held idea that this gene variant contributes to Alzheimer’s disease solely by promoting Aβ and tau accumulation4. Instead, it seems that BBB dysfunction might explain why APOE4 carriers are susceptible to Alzheimer’s disease. The authors’ findings might also explain why APOE4 carriers have worse outcomes following stroke or traumatic brain injury8 than do people who carry other APOE variants. However, as Alzheimer’s disease progresses, APOE4 could also slow Aβ and tau clearance, exacerbating declines in cognition.

Even more striking is the finding that early drivers of cognitive impairment differ between APOE4 and APOE3 carriers. Montagne and colleagues’ findings indicate that activation of the CypA pathway and pericyte damage might not be involved in cognitive impairment in people who carry the most common APOE variant*, APOE3*. But whether a leaky BBB caused by factors that are independent of pericytes (for example, damage to endothelial cells caused by Aβ1) contributes to cognitive impairment in APOE3 carriers remains unclear. The role of the BBB in APOE2 carriers, which was not assessed in the current study, also remains unknown. Although APOE2 is associated with a reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease compared with other APOE variants*,* this is unlikely to result from a more resilient BBB, because APOE2 carriers have an increased risk of microhaemorrhages, suggesting vascular frailty4.

Whether and how BBB breakdown leads to cognitive impairment also remains to be determined. Is it a cause or a consequence of the disease process? Evidence from mice indicates that some proteins in the blood, such as fibrinogen, damage the synaptic connections between neurons9. But a pathogenic role for these proteins in the human brain has not yet been demonstrated.

Irrespective of these questions, Montagne et al. have broadened our understanding of how APOE4 promotes cognitive impairment. They have also demonstrated that different APOE statuses can promote disease through different mechanisms. A deeper appreciation of how gene variants shape Alzheimer’s disease might prove crucial for more-personalized approaches to treating this prevalent and incurable disease.

See you tomorrow